If you had told me as a child that one day, I would be an entomologist writing a scathing retort to a New England Journal of Medicine Editorial, I probably wouldn’t believe you. First, I’d be confused because I didn’t know what an entomologist was, at the time, and secondly, because I was instilled with a strong sense of deference to authority as a child. Authority wants whats best for us, collectively, right? Authority makes reasoned, evidence based decisions that helps society be functional and productive, and since I cannot be an expert in all things, I should defer to the authority in a given area.1 It’s how living in a community, in a society, works best.

I think this is why I get so mad, so personally affronted, when I observe people in positions of authority who aren’t acting in ways that support the greater good, and instead are taking painfully obvious actions to maintain their own authority over a group.

In case you haven’t read it, I’m talking about this editorial.

If there ever was an authority I’d uncritically defer to, it is the New England Journal of Medicine.

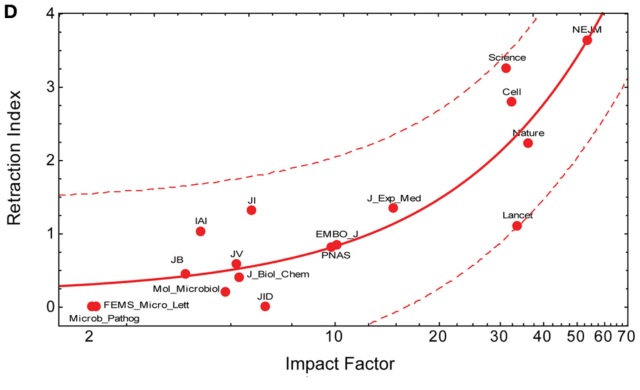

Well, this is awkward. From Brembs et al: Deep impact: unintended consequences of journal rank

…er.

Seriously, though. When it comes to contentious issues in medicine, NEJM is certainly regarded as an authority. But their recent editorial on data sharing, well, baby, you’re in my house now.2

There are many, many reasons that data shouldn’t be shared, and most many open science advocates are quick to acknowledge these issues- the editorial touches on some of these points. The big, obvious ones I see are confidentiality concerns and situations where releasing the data would otherwise present a hazard to the subjects under study.3 However, there is also a really important dynamic that’s often unacknowledged- the interplay between open science, privilege and power. Terry McGlynn explores this issue in more depth on his excellent blog post, but it can be summarized as such- the people in the most precarious positions- the students, the postdocs, the people working at small institutions who don’t have the resources to support many irons in the fire- are the ones that face the most risk when data sharing. The established scientists with large budgets at large research institutions, and the infamy and clout to defend their research ‘territory’ (if you will) have disproportionately little risk by sharing data. Yet, most outreach activities in the open science community target early-career scientists,4 and the most vocal cries against data sharing I’ve seen have come from the most established of the establishment. I take no objections to these arguments, and am actively working within the system to try and mitigate these risks and issues.5

So, this all being said, there are two main points that I take6 exception to in the NEJM editorial.

A second concern held by some is that a new class of research person will emerge — people who had nothing to do with the design and execution of the study but use another group’s data for their own ends, possibly stealing from the research productivity planned by the data gatherers, or even use the data to try to disprove what the original investigators had posited.

Read that again.

even use the data to try to disprove what the original investigators had posited.

Wow. So you mean to say that the data is only valid when used to support the collectors’ hypothesis? Do we need to do a little bit of a review of the scientific method here?

This statement irks me for several reasons- first of all, it assigns some sort of social value on the hypothesis. Everyone likes to be ‘right’ but hypotheses never are- they are either supported or not supported by the data (within the frequentist paradigm at least). However, data supporting one hypothesis doesn’t mean that hypothesis is true- it just means it was the best hypothesis tested in the study.7 If another person comes along and uses the body of available data to formulate a new, better supported hypothesis, this is not something to get sore over- this is a sign the scientific process is working. I know, scientists are people with egos, but if you really believed that your paper, your hypothesis was the final answer, shouldn’t science, I dunno, stop?

But it doesn’t stop. I think if you want to be the final answer in science, then you don’t really want to be a scientist. You just want to win.

The second bit that gets to me is more personal:

There is concern among some front-line researchers that the system will be taken over by what some researchers have characterized as “research parasites.”

This issue of the Journal offers a product of data sharing that is exactly the opposite. The new investigators arrived on the scene with their own ideas and worked symbiotically, rather than parasitically, with the investigators holding the data, moving the field forward in a way that neither group could have done on its own.

So, Hi! I’m Christie and I am a research parasite. I’m a pretty productive scientist for my career stage- partly because of what I often jokingly refer to as niche partitioning- I function as the data analyst on most of the collaborative projects I’m on. I see this as a mutually beneficial, heck, symbiotic relationship- and I believe most of the collaborators and data creators don’t feel my role is parasitic, exploitative or derivative. Yet NEJM seems to think this sort of positive relationship is some sort of exception. It also belittles the science I do-for example, one of my recent papers used three separate data sets, produced by others, for applications other than the data creators intended- and not all data creators ended up being authors on the final manuscript (although some did- based on their contribution to the scientific ideas, analysis and writing in the final paper). This paper is an original contribution to the literature that builds on the work of others, brings together the information we know about several domains to create new knowledge. This is what I grew up believing science was about.

What, precisely, does the typical “research parasite” look like to the editors of NEJM , I wonder? Evil monsters, lurking in the shadows, taking fuzzy pictures of your poster presentation so they can copy your graph? That grad student who can smugly stats faster than you, so she can ANOVA the crap out of your RCBD and get into Nature? Certainly not human beings with lives and families, who are interested in how the world works, and want to use our existing body of knowledge to ask more meaningful questions. Nah, that would never happen.

This NEJM editorial is not just about data sharing. It is about the scientific establishment using its power to foster the culture of fear and competitiveness that keeps them in power. And I, for one, am not buying what they’re selling.

—

1. this approach still tends to work reasonably well in the sphere of hair grooming. I usually just say to my stylist “You’re the expert, just do something low maintenance and flattering” and, as long as I don’t go to SuperBudgetCuts, the outcome is usually better than if I’d attempted to micromanage the situation.

2. If you take data sharing advice from me, you are not officially obligated to also take medical advice from me. Not that kind of doctor. No. Stop. I don’t want to see your rash.

3. Bahlai et al 2012, “A comprehensive listing of exact locations of endangered species often poached for the alternative medicine industry” in the Journal of Hypothetical Examples is, indeed, my most under-appreciated paper.

4. #OSRRcourse. Guilty as charged, officer.

5. This is a rant for another day, but I see the problem as there being a near total lack of incentives for open science practice within the traditional ways that scientists measure success. The establishment maintains control of these metrics, meaning that scientists who succeed by traditional metrics are the ones that gain power. Basically, a positive feedback loop of establishment power, corporate interests in the form of scientific publication, and people rewarding only the people who think most like them. This is wrong, and we need to rise up against it.

6. expletive deleted

7. “All models are wrong, some are useful” GEP Box, I believe. Models, mathematical formulations of hypotheses, are abstractions that can approach truth, but never really hit the truth asymptote, because nature isn’t neat and clean like that. But when you have a frequentist paradigm test of a hypothesis, you’re typically rejecting a null rather than directly testing your hypothesis. So basically, you’re saying “Well, it’s not NOT my hypothesis so my hypothesis is supported.”

Well said!

Interesting discussion Christie and I have three points to make, one of which is minor but is something which irks me so I’ll get it out of the way immediately: “symbiosis” does not mean “mutualistic”. The original and correct definition of symbiosis, from Anton de Bary in the 19th century, simply referred to any close biological relationship. Could be parasitic, could be commensal, could be mutualistic. It’s been misused and used to be seen (incorrectly) to be synonymous with “mutualism” but that was never widely accepted amongst those who study symbiosis, and has changed – see: http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ijb/article/view/21139

OK, rant over 🙂 More substantively I think one possible solution to concerns about data being “stolen” or “misused” is for journals to require that the original authors of large, re-used data sets be given co-authorship, unless they waive that right (in writing) to the journal. Manuscripts can only be submitted if all authors agree on the submission, so any concerns about misappropriation should be weeded out at that stage. If some authors misuse this and don’t include the “owner” of a data set as a co-author then that individual can lobby a journal for a retraction. It’s not perfect, and I realise that there are sometimes issues over who owns the data, but this should be a robust system that is self correcting to some degree.

My other point is that, whilst I don’t worry about “research parasites”, I do have concerns that in ecology there is emerging a group of younger scientists who have no field or lab experience whatsoever, they know nothing about any of the systems that they analyse or write about, all of their research is done in silico. That can’t be good for the field or for their future careers; a couple of the later paragraphs in this old post of mine discuss this issue: https://jeffollerton.wordpress.com/2014/07/10/7-minutes-is-a-long-time-in-science-7-goals-is-a-big-win-in-football-bes-macroecology-meeting-day-2/

I’m not sure what can be done except for supervisors to encourage their research students to get out and get their boots muddy (or at least their hands wet in the lab!)

The use of the word “symbiotic” was parroting its use in the original editorial- my tongue was firmly in cheek.

I disagree strongly with you on the idea of ever requiring authorship for data producers. Yes, data producers play an important role in all aspects of science, however, my definition of an author is a person who made a substantial intellectual contribution to the given paper (for simplicity let’s just say it’s a paper as a measure of incremental advancements in science). it’s just like when we write papers that build on and test the ideas of scientists before us- yes, we are using the work, the blood sweat and tears, the effort, but the correct way to acknowledge those contributions is through citation, not through offering authorship. It’s only appropriate to offer authorship in this situation if the creators of this previous work have actively contributed to the current paper. In fact, this is not only appropriate, it’s good science- it allows what we know to be re-interpreted through new paradigms, re-evaluated, and indeed, allows young scientists to disagree with their predecessors without being held hostage by some form of duty-authorship. This is not to dismiss the work of data producers (nor authors of previous papers)- I am a person with a perhaps inordinate respect for data- and it’s also bad science to not cite the contributions made by those before you.

You can probably see where I’m going with this- data needs to be citable. In fact, there are numerous efforts to do so which are increasingly being adopted, for example, when you submit data to Dryad you get a DOI, and your data becomes a citable entity, and figshare can be used the same way, but for an even wider variety of research products.

Finally, I think you underestimate the lab and field experience, and the quality of output that early career scientists are associated with these days (for example, I am the most ‘in silico’ ecologist I know and just yesterday I was down in the insectary, drooling into a mouth aspirator while I handled my colony of ladybeetles). The reality of the job market today is that scientists can’t get by with JUST lab/field skills, just a great publication record, just programming skills, etc, etc- we have to be all these things. I’d argue that in many cases, early career scientists are actually acquiring MORE field (and everything else) experience than they were in the past because of the extended training period now common before an ECR is considered competitive for a tenure-track position in the current market.

Re: symbiosis – yes, I was referring to NEJM’s use too.

We may have to agree to disagree regarding the data-authorship question. The collection of new data is (as you say) important and, I’d argue, the “substantial intellectual contribution” to the paper that you are looking for – good data don’t just appear, their collection requires thought and care, as well as effort. Having citable data is not the answer – the original papers in which they appeared are citable, and for unpublished data a single citation is hardly a fair trade!

As for your last comments, my point was that whilst, yes, there’s lots of good training and experience going on, as you describe, there’s also bad practice too. And it’s the grad students who don’t get that wider experience who will be at a disadvantage in the job market you describe. But they will also be at a disadvantage if they are not included as co-authors on papers that use unpublished data that they have collected.

Ah, I think I see where we’re misunderstanding each other. I am not arguing for the forced sharing of unpublished data. I am, however, arguing that data should accompany publications as a general rule, and when that data, like any part of a scientific contribution, is used in support of a subsequent paper, the authors are obligated to cite, but not necessarily offer authorship in this subsequent product. I think the original authors should have options regarding how they publish their data – ie attached to the paper as supplemental materials, in a separate, citable data repository, but the data needs to be made available. Kristen Briney gave an excellent TedX talk about this: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=dXKbkpilQME

“I think one possible solution to concerns about data being “stolen” or “misused” is for journals to require that the original authors of large, re-used data sets be given co-authorship, unless they waive that right (in writing) to the journal.”

I disagree very, very strongly with this proposal, for at least two reasons. First, all “courtesy authorship” is an abomination: the generators of the data get their credit in the form of citation, and pretending that they are authors is simply wrong. Second, the convention you propose gives the originators of the data a very easy way to block any publication they don’t like.

See Christie’s response, Mike. I was referring to unpublished data, which perhaps I didn;t make as clear as it could have been. I wouldn’t consider that “courtesy authorship”.

I agree that the case of unpublished data is different. (But then, how would the new author even have a copy of the unpublished data if not because he was collaborating with the person who generated the data?)

Oh, there are a myriad of ways: unscrupulous supervisors and colleagues; offers of “collaboration” that don’t work out that way; extracting data from unpublished tables and figures in presentations using, e.g., DataThief; ditto from blog post; etc.

Well, those are all flagrantly unethical anyway. We don’t need new rule to make such behaviour unethical.

Thank you for laying this out. I could hardly believe my eyes as I read that editorial — the most flagrant advertisement I have ever seen for the entrenchment of existing power structures at the expense of actually advancing science. I hope the authors are ashamed of themselves, and the journal ashamed of having published their unbalanced, ignorant, reactionary rant.

Reblogged this on Green Tea and Velociraptors and commented:

Great counter-piece to that daft NEJM editorial doing the rounds in the social media-verse.